From fire extinguishers and sprinklers to lifeboats and life jackets, ships of all shapes and sizes must be equipped to respond efficiently and effectively to any potential hazards that could put the lives of those onboard at risk.

However, it is not just onboard safety that is important. Ship operators must also consider the appropriate actions to take if a member of a vessel finds themselves overboard.

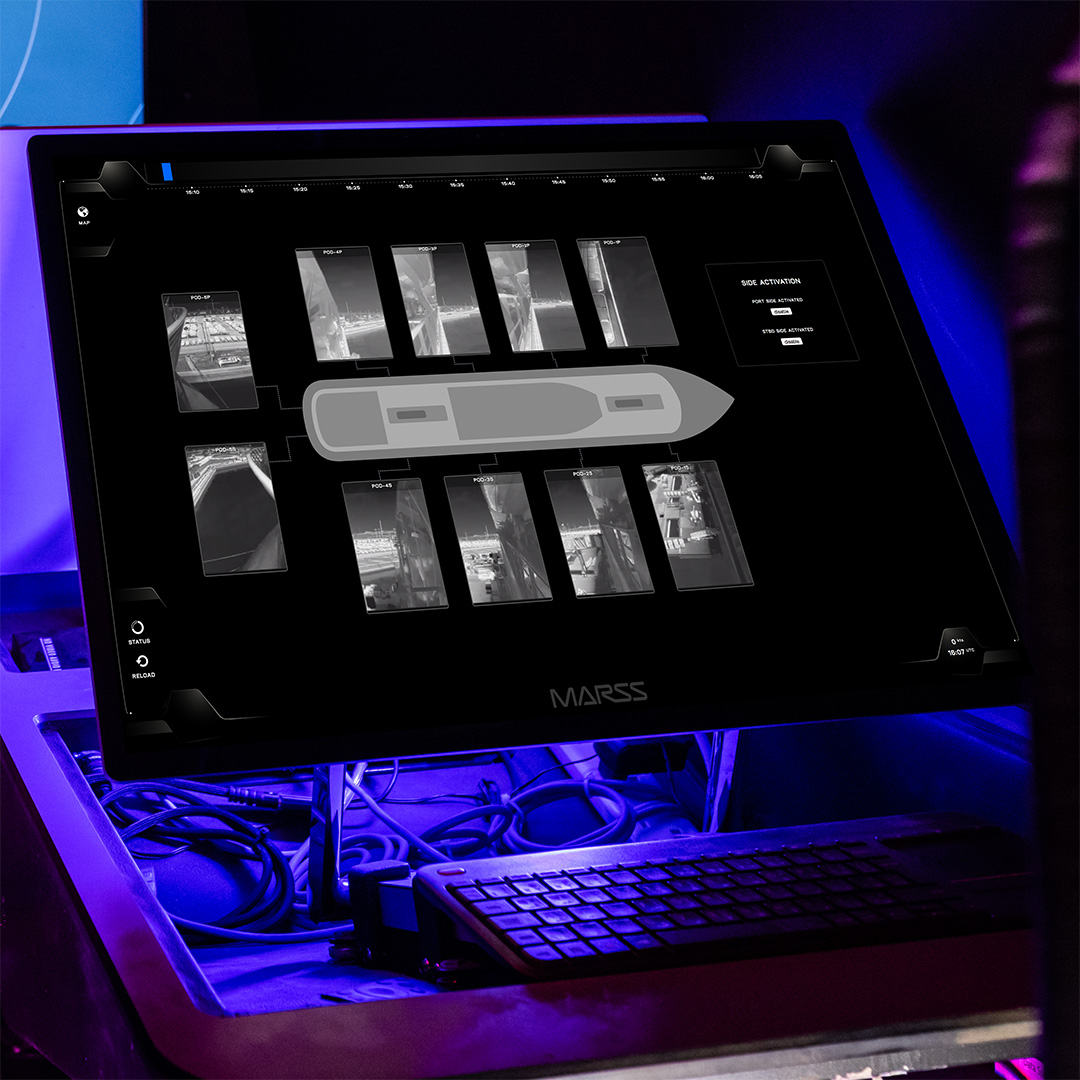

Man-overboard (MOB) technology is an area that’s attracting increasing attention in the marine industry. Novel capabilities and solutions are being actively designed, developed and deployed to better detect and locate those who have fallen from a ship.

Incidents of this kind are both particularly prevalent and dangerous in the cruise industry. Nearly 400 people are reported to have gone overboard between 2000 to 2020, with around 18 to 20 incidents occurring on cruise ships in an average year.

Some initial steps have already been taken to reduce individuals’ potential to fall overboard. In 2010, the Cruise Vessel, Security and Safety Act (CVSSA) was amended to stipulate that rail heights be no less than 42 inches, for example, making it highly unlikely that any normal adult persons should fall off a vessel simply by leaning over the side.

But because incidents continue to occur – be they accidental or out of choice – ships need a means of quickly detecting when and where an individual has fallen into the water.